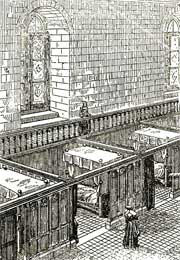

How did monks get into the Infirmary for treatment? Rules varied according to local practice. It was a wise Infirmarian who ensured that he had beds in reserve. A system to control entry would be desirable. Westminster had what they called "outside of the choir" patients (perhaps blood-letting patients)who were like day visitors, using the miserichord and parlour and then other "in patients" who were there night and day, often for 2-4 days. In the 14th century any monks at St Augustine's Canterbury who were deemed ill enough could be supplied with a fat capon, wine and candles and spend 8 days in the Infirmary. I hope this was not abused!

Discipline was slightly more relaxed once inside the Infirmary: for example clothing regulations. Talking was allowed but silence was demanded after the office of Compline. Examples have been found of "old stagers" causing dissention by with their constant reminiscing "Licentious games were forbidden". It is easy to imagine that as monastic discipline declined, a spell in the Infirmary became an attractive option. The seven Offices of the day were supposedly said in the Infirmary so these will have started at dawn It looks as though hospitals still remember this as patients are awakened at 6.00 and get tea and then have a two hour wait before breakfast!

The Miserichord (dining room)would serve meat but most crucially there was choice and diet could match individual requirements. Apparently at Westminster some individual dietary requirements had to receive permission from the Abbot or Prior. There was a case where the patient declined to drink beer and the prior substituted wine. The accounts show 10 shillings spent on wine.

We must remember that illness was often seen as Divine judgment and a way for the soul to be purified through individual suffering. (This idea did not go down too well after the Black Death of 1349) Individuals would seek religious cures. This was still the background for the work of the Infirmary. Patients would be party to the continuing round of Offices in the Infirmary and this was part of the treatment.

What sort ailments might have been common? Early rising and vigils in a freezing church and austere way of life could have led to mental and physical collapse. The harsh diet could lead to stomach problems. The Cluniacs got back trouble from too much manhandling of heavy bells. Also the demands of the liturgy with the excessive amount of chanting contributed to congestion and coughs. The vigils took their toll too with the poor lighting and dust leading to eye problems. The great Abbot Peter the Venerable suffered from catarrh which affected his voice and prevented him from preaching.

Research from records kept by the Infirmarer at Westminster 1383-1417 found liver complaints, possibly from large intake of ale and hyperostosis (too much growth of bone tissue) maybe connected to obesity. Also a lot of treatment of disease in the shinbone (morbus in tibia) which were probably varicose ulcers. These could have worsened with the constant standing for Offices, and also the dietary lack of vitamin C. From figures in Barbara Harvey's survey of Westminster Abbey 1375-1529 some 40% per year of the monks were admitted to the Infirmary during the year and most were not there for more than 8 nights. This is not including day patients. She thinks this shows resilience bearing in mind the lifestyle and hazards of the day.

Infirmaries had to cater for a variety of serious illnesses and diseases. Leprosy was a common problem and we shall return to this in a later post about public health care. Caring for such diseases was a factor in the drive to compartmentalise the large infirmary halls.

The next stage was to work out a physical cure if this were necessary. The Infirmarian would be advised by a physician who was "hired" for a fee to make visits. He would make the diagnosis and recommend medicines or other measures. The medicines might be supplied by an apothecary from outside, particularly for complex or time-consuming recipes. He might supply cordials which he had made up, or Lozenges and pills. In some cases he might use items from the herb garden in the monastery.The Infirmarian and his assistant may also have dispensed medicines, using their herb garden. If surgery was needed a surgeon would be brought in. Usual operations were for fractures, wounds, ulcers etc. but were rarely abdominal. There were no real anaesthetics. The surgeons were paid for each operation. All these persons were seen as channels for divine healing.

It seems that the actual operation of health care varied across the various monasteries. The Synod of Clermont in 1095 had forbidden medical activity by clergy, but this was not the end of that story. The ability to have physician, surgeon and apothecary all easily available would obviously be very different in Fountains Abbey as opposed to Westminster. Practices also developed during our period. (1066-1539)

In the 11th century monasteries had been the only place for medical learning in western Europe. A school of medicine seems to have grown up at Salerno in southern Italy in the 9th and 10th centuries coming to flower by the end of the 12th. The Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum or Salernitan Rule of Health may have originated from the 12th or 13th century. Written in rhymed verse it is likely to be founded upon the teaching employed in the Salerno school. There was a succession of monk physicians emanating from Salerno and other medical universities., like Montpellier, Bologna and Paris.

Abbot Baldwin of Bury St Edmunds was the consultant physician for King William I and Bishop Arfust of Norwich also was treated by him for an eye injury..St Albans had a family of physicians trained at Salerno. Warin was the head of these and was later to become Prior and Abbot. (1183-95). His successor John de Cella (1195-1214)was also a physician. Some monasteries had their own physician and these individuals were greatly prized.

Herbal medicine was very important. Back in the ninth century Walafrid Strabo (809-49) from the Rheichenau island on Lake Constance in southern Germany had described 23 herbs which could be used. Monks were seldom physicians, but the use of herbal medicine by monks was widespread. Ancient practice by other civilisations could be called upon and the work of Hippocrates (460-377 BC) and Dioscorides (40-90 AD) was crucial. Monastic gardens were developed in Italy from the 6th century. Herbal sections became separate so that particular plants could be chosen for recipes. In our period (1066-1539) a monastery was not complete without a herb garden.

Books about the use of herbs were written. The Regimen Sanitatis Salernitanum mentioned earlier for example. St Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1190) described 250 plant species for their healing and nutitional value. This was broken down into 28 for a basic medical kit : galgant alpinia, horseradish, cinnamon, summer savory, basil, mugwort, garlic, nutmeg, mustard, gentian, cloves, hyssop, ginger, dill, bay leaf, lovage, garden orache, peppermint, pepper, parsley, nettle, watercress, sage, chives and tansy. Headaches and aching joints could be eased by sweet smelling herbs like rose, lavender and sage. Fever could be reduced using coriander. Stomach pains could be treated with wormwood, mint and balm. Mint was used to treat venom and wounds.

I recommend you look at this post by Dr. Christopher Monk on his blog Blogum scribum which details this in detail brilliantly.

The photos below show myself as the Infirmarian in our Medieval Munchies weekend 18-19 September 2021 at St Albans Cathedral.It was great fun. I seem to look rather like the mad librarian monk in the film "Name of the Rose"!

Some sources

Bottomley, F. Abbey explorer’s guide (Otley, 1995)

Braun, H. English abbeys {London, 1971)

Clark, J.G. Benedictines in the Middle Ages (Woodridge, 2011)

Clark, J.G. and Preest, D. eds. Deeds of the Abbots of St Albans (Boydell Press, 2019)

Crossley, F.H. The English abbey 3rd ed, (London,1949)

Evans, J. The Romanesque architecture of the Order of Cluny (Cambridge, 1938)

Harvey, B. Living and dying in England 110-1540 the monastic experience. (Oxford, 1993)

Kerr, J. Life in the Medieval cloister (London, 2009)

Knowles, D. ReligiousOrders in England vol 1-3 (Cambridge, 2008)

Leroux-Dhuys, J-F. Cistercian abbeys : history and architecture (Cologne, 1998)

McAleavey, T. Life in a Medieval abbey (London, 1995)

Mountford, A. Health, sickness, medicine and the friars in the 13 th and 14th centuries. (Abingdon, 2004)

Parry, A. ed. Rule of St Benedict (Leominster, 1990)

Rosewell, R The Medieval monastery (Oxford, 2011)

Williams, D.H. The Cistercians in the early Middle Ages (1998)