|

| My model of Ely Cathedral : also an Abbey - keeps cropping up in this post |

The 6th century Rule of St Benedict speaks of one meal a day in winter and possibly an additional light supper in summer (Easter to mid September). By the 11th century or earlier Festive occasions warranted little extra courses known confusingly as pittances. We think of a pittance as a small or inadequate amount of money. Pittances began in monasteries as a bequest left by someone to provide extra food at a particular time. We should also remember that there were over 100 feast days and saints days in a year. The Rule prohibited the eating of flesh meat. This could only be waived in cases of the very weak and sick. When I eventually post about meat eating we shall see that it was the general trend for Orders to begin very hardline and gradually relax their discipline. This is not surprising because St Benedict was writing for monks in southern Italy with its different climate. For example the Cistercians began in the 12th century with no fish eating but later it was a major staple of their diet.

|

| Franciscans fishing in a painting from 1880 by Walter Dendy Sadler called "Thursday 1880"Photo @Tate Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 unported) For more info click here |

Therefore fish became a popular option for all the Orders and it became customary on Fridays, Saturdays and Wednesdays and all six weeks of Lent for much of the Middle Ages. The Cistercians, so stringent in their discipline, had widely taken to fish before the end of the 12th century and into the 13th.Outside the monasteries lay people could usually only get salted and pickled herrings and dried cod which was stiff as a board. Monasteries enjoyed much more varied and exotic offerings as we shall see. At the abbey in Westminster by the early 16th century fish was served on as many as 215 days a year. On Fridays there would be 2 main fish dishes, and on other fish days perhaps three fish dishes. Winchester Abbey monks consumed fish for 165 of 278 days (59%) from 12 Dec 1514 to 19 Aug. 1515. These may have been exceptional but give some idea of how important fish had become in the monkish diet. Generally fish were used for the main meal rather than the pittances. The latter is where shellfish like cockles, mussels, whelks or oysters would be served. Splendid fish like pike, sturgeon and turbot might appear at major feasts, or for visitors. We are able to build up a picture of how it worked through the evidence left in the accounts of the cellarer (in charge of food and drink)found in some monasteries and manorial records. Also critical comments left after visitations (our Abbot Thomas de la Mare (1349-1396)made many visits to other monasteries inspecting and reporting on disciplinary lapses). Finally, there is the evidence from excavated food remains on monastic sites and from the diet and health of monks derived from skeletons found.eg Westminster.

What would be on the menu?

The abbot’s kitchen would be dealing with the more fancy or rare fish especially for visitors. The monks might get some of these rarities as a pittance rather than a main dish. For example conger eel would be a treat to monks but not so in the abbot’s kitchen. Helpings were likely larger than we would expect - perhaps 1.5 lb of fish per person compared to 1.25-0.5 lb in restaurants today.

Here are some sample dishes::

Red Herring with mustard

Eel with pepper, cumin and saffron

Eel tart

Douce tygre (fish in sweet and sour sauce)

Oysters in cevey (stewed in wine)

Dressed crab (blended with vinegar, ginger, cinnamon, sugar and wine and served hot)

(For more ideas see a wonderful little book about Evesham Abbey : Flans and Wine : food cookery in a medieval monastery by Brother William of Berneslei : translated by David Snowden)

How did they get the fish?

I will now explain how such a lot of fish could have reached the monkish table. Fish could come from local rivers or the coast where the monastery had fishing rights. It could be handed over as a gratuity or a payment in place of a tithe or toll. Fountains Abbey in Yorkshire had fishing rights on Malham Tarn. It also had rights on the River Tees which it shared with Rievaulx Abbey. These were Cistercian foundations and the fishing would have been done by the conversi (lay brothers). They might also do the drying and salting. Evidence of this of this has been found in the Oldstead Grange (monastic farm) at Byland Abbey in Yorkshire. At St Albans there were rights along the Ver to near Park Street and the natural lakes, still popular today. The prior of St Alban’s daughter house at Tynemouth (the mouth of the river Tyne near Newcastle), built a port for fishing and trading. The abbey at Chester had a boat on the Dee and a ship with 10 nets off the island of Anglesey for some of their supply. St Dogmaels near Cardigan in Wales had fishing rights on the nearby River Teifi or from monastic fishponds. Some fish might be fresh from either source but most would be cured some way before or after purchase.

I was born in the Fens in East Anglia and here much of the land was very low or under water with amazingly abundant fish of many kinds. Contemporaries were staggered by the amount of fish there. The Abbots of Ramsey and Thorney made agreements between themselves about local fishing rights. Matters were not always cordial with secular landowners and in a legal dispute with a local lord of the manor, the Abbot of Crowland was found guilty of trespass and fined heavily.The Cathedral/Priory at Ely had an unusual way of obtaining fish. Locals would pay their dues to the priory with fresh eels in “Sticks” of eels. (25 per Stick).This may be the origin of the name Ely. Nor was this unique : the Upwell/Outwell area outside Wisbech (Cambridgeshire) paid Ramsey Abbey 60,000 eels a year! Castle Acre Priory in Norfolk received 2000 eels from nearby Methwold.

|

| Primitive ways of catching eels |

|

| Nets for catching eels |

Monasteries would seek supplies at markets or use suppliers who brought goods to them. At Westminster in the later Middle Ages the cellarer would perhaps go down to the city market every day. The fish he bought would likely come from the fishing grounds off Kent and Essex. Much of it was brought into Queenhythe a small islet in the Thames and processed there (pickled, salted, or smoked). It was hard to transport fresh fish very far inland and monasteries near the sea must have had an advantage. E.g. Tynemouth. Even so I have read that Syon Abbey in West London had fish from Scarborough in Yorkshire and Iceland!

Fishponds

There was a popular view that most of the fish consumed in monasteries came from their own fishponds. It is now believed that the first fishponds were founded by secular landowners. Monasteries found them useful and they became common by the end of the 12th century. Some early examples were in fact gifts from local laity. It is clear that these ponds could seldom have provided enough fish to support a monastery. The idea that there was surplus for selling on to outsiders is now discounted. They were like store cupboards used to provide stocks of particular fish for special occasions or visitors. (Rather like posh fish restaurants keep fish in a tank for customers to choose). It is likely that the sea provided more fish for the monasteries than freshwater rivers and lakes and ponds least of all. Fishponds were costly to build and maintain and might involve negotiation or disputes with local landowners. Cistercian foundations in their remote locations would have found it less hassle to start fishponds than the older Orders in their more populated or urban environment. Canterbury and Glastonbury had only one pond each but the Augustinian Maxstoke Priory in Warwickshire had eight inside the precinct and two more outside. Ponds could also be associated with local granges (farms owned by the monastery) and were run by lay folk. All ponds should be flushed out regularly and this had to be assured by a local water supply and good management from the monastic community. For example bream and pike had a 5 year growth cycle and required a cleaning of the pond every five years.

|

| Fishpond today at Waltham Abbey |

|

| Fishing at Waltham Abbey |

It was common for monasteries to have mill ponds. These were a body of water, often constructed through the building of a dam or weir across a stream. They were then used like a reservoir to power a water mill. Stoneleigh Abbey at Crayfield in Warwickshire housed perch, bream roach and pickerel in the 1380s. At some time in the later Middle Ages the Abbey watermills in St Albans along the Ver provided 1000 eels a year.We had several fishponds here at St Albans along the southern side of the Ver and it is possible that a building on the site of the Fighting Cocks pub was used for fishing tackle.Today the river Ver is much smaller and more like stream. The recently constructed bypass sluice near the Fighting Cocks reminds us of the importance of the mill.

|

| Views around the Fighting Cocks, St Albans |

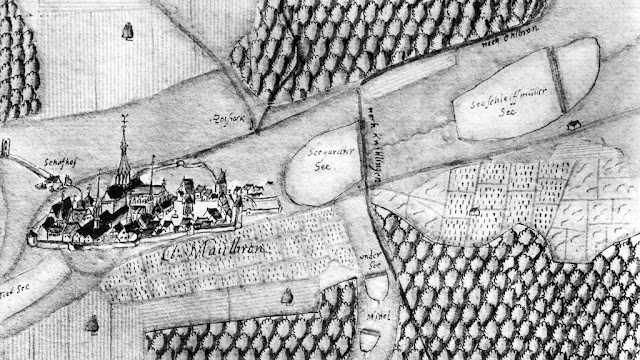

The Cistercians regarded fish as “river fruit” and there is a great example of a pond system at Maulbronn in south Germany. The unique system there has 20 reservoirs and ponds, of which three remain today. The fish raised were mainly eels, pike and carp ; also tench, bass and roach.

From the Baroque period there are examples of ornamental fishponds in monasteries in the Holy Roman Empire. Eg Wessobrunn in Bavaria on left below seen last years and Kremsmunster in Lower Austria which I hope to see one day!

|

From my researches I have found mentions of the following : (bear in mind availability would vary over the country)

Barbel,,Bream,Carp,Chub,Cockles,Cod,CongerEel,Dace,Eel,Flounder,Grayling,Gudgeon,Herring,Lamprey,Mackerel,Minnow,Mullet,Mussels,Oysters,Perch,Pickerel,Pike,Plaice,,Roach,Ruff,Salmon,Seal,Skate,Sole,Sturgeon,Tench,Turbot,Whelks,Whitebait,

Whiting.

In some places barnacle geese and puffins counted as fish because they were created at sea, also beavers!

Conservation of Fish

Fish consumed in monasteries was mostly cured : fresh fish was more rare. So how were they conserved? The use of salt was critical. It was used as preservative, and flavour enhancer.The salting process meant that the fish were covered in salt which absorbed the water in the fish, and this prevented growth of bacteria and fungi. It also slows down the oxidisation process and the fish from becoming rancid. There were many types salt available. The finer ones worked quicker. Lighter salting or powdering was used for short term preservation. The aim was to make the salt act like a dry cure. It could be combined with smoking

Rock salt was plentiful in Cheshire and Worcestershire. At Nantwich streams were diverted and the salt water was collected and boiled in flat pans with a protein eg. ox blood which collected impurities that could be skimmed off later. The evaporated water was put through wicker baskets, dried and loaded onto a pack horse. Pack trains distributed salt around the country. The salt would be in cones, and pieces had to be chipped off. It was not until the 19th century that an additive made the salt free running. There was sea salt gathered in the Fens and processed in shallow pans.

Salt was expensive because it was taxed in other countries. Then by the late Middle Ages fish farming had developed leading to more sea vessels and more salt to preserve the fish.

Salt was useful in other ways. At Winchester in 1305 the butter produced in the abbey used 1 lb salt to 10lb of butter : ie 10% compared to today’s 2%!

Dried and salted fish might be bought annually in large amounts by some monasteries.

Smoked fish had to be lightly salted first. In our climate this was necessary to keep bacteria under control. Drier places could preserve fish by air drying and were able to smoke fatty foods with no further help.A smoking house for fish has been excavated at Byland Abbey in Yorkshire. Salt cod and herrings were very popular. To process herrings, they were first gutted, opened out and laid in layers separated by coarse salt in barrels. This drew the juice out of the fish, and mingling with the salt became brine. Twelve of these might be packed tightly in a small watertight barrel.

Cod would be cleaned and filleted and both sides rubbed with dry salt and then hung up to air dry. The moisture dripped out, flesh dehydrated and bacterial activity slowed down. This made the fish extremely hard and to be used it hard to be soaked for 24 hours with changes of water to remove salt and rehydrate it. We can still see this process today in the salt cod (Bacalao) so beloved by the Spanish and Portuguese.

|

| Piles of Bacalao for dinner |