"Scandalous ; how did they do it? And the nuns too...Maybe it was weaker! But they couldnt drink the water could they?"

St Benedict does not speak of beer in the Rule, but remember this was written in Italy in the 6th century. He does mention wine - "half a pint daily is enough" I shall cover wine in a later post... But I think the message is clear : Western monks have not been traditionally denied alcohol.

Monks have been brewing beer since at least the 5th century and at the peak over 600 monasteries were doing it. It was customary to try to be self-sufficient and production had to cover pilgrims and visitors too.They believed they were doing God's work and therefore it should be done well and be good. The cellarer and sub-cellerar were expected to ensure ale was well made, a good colour from good malt with a good flavour. Punishment from senior monks could follow poor practice.In 1515 the ale given to monks at Ely was said to be only fit for pigs! The Prior was told to improve it forthwith so the monks had no reason to go inth taverns in the town! In the quest for making more and more beer they eventually added hops in the 15th centuryto balance the sweetness of malt and act as a preservative.

I think it is better to think of the beer which monks drank as liquid bread. In fact after bread itself beer was the next most important way to get the calories, minerals and vitamins to keep them going.

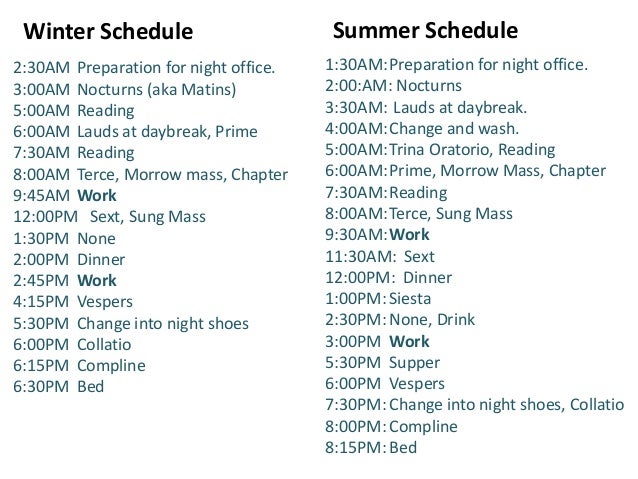

Ale plus mixed grain bread would provide much of what a person required except for vitamin C. Imagine a monk in a cold monastery chanting hour after hour. This took stamina: the standing, sitting, kneeling plus the amount of singing. Perhaps all 150 Psalms in a week! They would need a drink all right! I believe it was this liquid bread that is the key to how they coped.In the late 15th century monks at Westminster were allowed a gallon (yes 8 pints) a day. Outside meals they might even have more, especially if they had had to sing exceptional psalms. The precenter could expect more after singing a long office on a feast day.It has been estimated that alcohol accounted for 19% in energy terms in a monk's diet.Contrast this with a national average today of 5%.

Clearly the beer they drank was weak by modern standards, maybe like our present pale ale. I am still somewhat puzzled how they managed to down 8 pints in a day with only one major meal plus perhaps a light breakfast and a drink at the end of the day after Compline.The latter evidently became the norm in some institutions (even the nuns at Ankerwick Priory apparently) and had to be discouraged. Otherwise I imagine monks downing lots of pints at the main meal and or crafty pints at intervals somehow somewhere. And those main meals were meant to be silent....No wonder there were reports of instances of strange hand signals and noises at meals...It remains a puzzle. and I believe 8 pints was well above the norm for most places at most dates. It might be thought that the senior monks were the worst culprits but not always, for Abbot Wulfstan of Worcester pretended to drink ale or mead after dinner and in fact it was water. Only his servant knew.

People in the Middle Ages will have had a tougher constitution than us, and were able to eat and drink things which we would or could not safely stomach. Water was dodgy but did vary. Stream or pond water was better and different from brackish and salty sea water. Water was sometimes boiled before drinking. Also it was used to dilute other drinks like red wine.

It was ale which was made first from various malts including barley, wheat, oats and mixed grains. It was made in smallish batches because it had to be drunk within 2 weeks. It could be flavoured in various ways with herbs, nettles etc. This could make it thick, nutty, light, or flowery. Often ale had yeast included. These yeasts might be in the air, or on grains or fruit and would affect the flavour. Our modern yeasts come from Germany. In the Middle Ages we would have used our own milder yeasts for ale.

Clearly the beer they drank was weak by modern standards, maybe like our present pale ale. I am still somewhat puzzled how they managed to down 8 pints in a day with only one major meal plus perhaps a light breakfast and a drink at the end of the day after Compline.The latter evidently became the norm in some institutions (even the nuns at Ankerwick Priory apparently) and had to be discouraged. Otherwise I imagine monks downing lots of pints at the main meal and or crafty pints at intervals somehow somewhere. And those main meals were meant to be silent....No wonder there were reports of instances of strange hand signals and noises at meals...It remains a puzzle. and I believe 8 pints was well above the norm for most places at most dates. It might be thought that the senior monks were the worst culprits but not always, for Abbot Wulfstan of Worcester pretended to drink ale or mead after dinner and in fact it was water. Only his servant knew.

People in the Middle Ages will have had a tougher constitution than us, and were able to eat and drink things which we would or could not safely stomach. Water was dodgy but did vary. Stream or pond water was better and different from brackish and salty sea water. Water was sometimes boiled before drinking. Also it was used to dilute other drinks like red wine.

In the 15th century hops began to be added and this made the drink more bitter but enabled it to be kept longer periods and made in much larger batches.Abbeys were in the forefront of this change and invested in large vats, tubs and barrels. However ale was still populat as some monks would prefer the sweeter ales to the newer bitter beers.

So monasteries and nunneries had their own brewhouses. It was big business and monasteries needed to invest in them. Norwich Priory in 1263/4 spent £2.15.11 on materials and £1 on building a new lead roof for the brewhouse and bakehouse (these were often grouped together).It was a lot then! In the later Middle Ages monasteries would invest in large vats, tubs and barrels. Big cellars could contain many barrels of

the hopped beers.

What did brewhouses look like? Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire was an Augustinian nunnery. The new owner after the Supression of the Monasteries in 1539 was Sir William Sherrington. He kept a brewhouse which still has its furnace, vats and cooling tanks which replicate the medieval ones.

the hopped beers.

What did brewhouses look like? Lacock Abbey in Wiltshire was an Augustinian nunnery. The new owner after the Supression of the Monasteries in 1539 was Sir William Sherrington. He kept a brewhouse which still has its furnace, vats and cooling tanks which replicate the medieval ones.

|

| Lacock Abbey brewhouse : mash tun cooler and fermenting vessel (Jordin57 on cc flickr) |

Brewing was most often done by women - perhaps the wives and daughters of the official named brewer,

Going back to really ear;ly monastic practice. The famous 9th century map of St Gall in Switzerland shows 3 breweries - one for visitors, one for pilgrims and one for the poor. By 800 this had become an imperial abbey. I am not suggesting that Emperor Charlemagne actually came through and binged in the abbey but it is possible to suggest via this plan that by 829 beer was being brewed here. It is a matter of opinion whether the abbey looked something like the plan or whether this is an idealised abbey plan.

|

| Model of St Gall derived from the plan |

|

| Kloster Weltenberg |

Kloster Andechs with its double altar and grave of Carl Orff boasts a huge beer garden serving the light Andechser Bergbok Hell and dark Andechser Doppelbock. Beer production started there 1391.

Now we have English Trappist monks making beer in England for the first time! Tynt Meadow is mahogany in colour with aromas of dark chocolate, liquorice and rich fruit flavours.Made by the monks of St Bernard Abbey near Coalville, Leicestershire it will be something between a strong brown ale, a barley wine and a dark porter. Sounds lovely....It is replacing their dairy farm which was not sufficiently profitable. It must still be secondary to their normal work and way of life and help to fund their living expenses, the grounds and various charities.

Brewhouses were obviously common in the Middle Ages. They are still being found. For example excavations have discovered that Bicester Priory had a brew house which was excavated in 2013 under the site of a former care home.

What about St Albans?

We know there was a brewhouse for the Abbey and it may have been situated near the river Ver near the mill beyond present Fighting Cocks pub. It was a rather larger river than the present stream! We know a little about standards : Matthew Paris tells us in his Chronicle that Abbot John had to improve the beer drastically as it had become unacceptably weak.He therefore set aside 1000 loads of barley and oats suiable for making better beer. Presumably standards improved and the monks became happier.

Reminders of earlier ale houses are around me every time I step into our city. Alleys around the market place with names like like Lamb Alley and Boot Alley. As I go through an ancient alley featuring a 15th century grotesque.into French Row I feel very near to the generations who have smoked or relieved themselves here.

St Albans has a special in the beer world as the birth place of CAMRA. (Campaign for Real Ale) On 20 November 1972nMichael Hardman, Graham Lees, Jim Makin and Bill Mellor held the first Branch Meeting of what was to become CAMRA in the Farriers Arms in Lower Dagnall Street. The ai,m was to champion te cause of real ale, cider and perry and support a thriving pub in every community. There are now over 190,000 of us who are members! The annual Beer Festival in the main assembly hall of the town (the Arena) in late September seems to get bigger every year with every nook and cranny in the building plus a sizeable overspill outside filled to bursting.

|

| I dont think I am on this photo of our CAMRA St Albans Beer Festival! |